Well, that was the MOOC that was!

According to the course convenors, Dr William Cope and Dr Mary Kalantzis, around 4000 participants signed up to become the second cohort on the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign‘s e-Learning Ecologies MOOC on Coursera, which is quite modest compared to the University of Edinburgh‘s e-Learning and Digital Cultures MOOC (over 40,000). Nevertheless, its says less about the quantity and more about the quality. This MOOC did tide me over whilst I was waiting to attend the seventh and final module of the taught part of the Doctorate in Education (EdD).

Course Structure

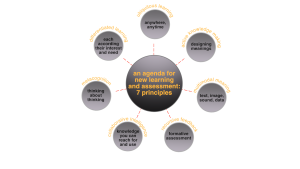

The course is centred around the notion of the seven e-affordances framework that features in Cope & Kalantzis’ (2012) New Learning project. Week 1 provided the overview with weeks 2 to 8 focusing upon

each of the seven e-affordances. Each week, the student would be presented with a 20 minute video (usually broken into a number of ‘episodes’); and depending on the level of engagement the student opted for, depended how much time they would spend on the tasks and activities. I have to say that I was very impressed with the “3 levels of participation” and would strongly suggest that other online course providers should provide something similar. For this course, the levels of participation were levelled in the following way:

-

New Learning and Assessment: Seven Affordances Framework (Cope & Kalantzis, 2012) (O)verview: Spending roughly 1-3 hours / week watching some videos, reading some articles and participating in the forums.

- (I)ntermediate: Spending roughly 3-8 hours / week watching some videos, reading some articles, participating in the forums, and posting an original contribution.

- (A)dvanced: Spending roughly 8-10 hours / week watching all of the videos, reading all of the articles, participating in the forums, posting an original contribution, and creating a peer-reviewed case study (You would have to do the “Advanced” level to qualify for the verified certificate).

I opted to undertake the Intermediate level (or at least a variation of it), posting my “original” contribution to the Coursera and Scholar platforms as well as my blog. In reality, only week 1 had a number of articles that had to be read, after that weeks 2 to 8 were exclusively video-based and taking part in several very short and pithy polls.

Cope & Kalantzis were at great pains to explain that there was nothing particularly innovative with these seven e-affordances, indeed some were quite old concepts. What was, of interest, is the ease in which current and emergent educational technologies are able to incorporate these affordances to open up educational opportunities and encounters that could be described as “New Learning”.

Video Lectures: The Good

One of the criticism of the first cohort of the e-Learning and Digital Cultures MOOC was that students wanted to see videos of the course tutors “teaching” something (though the tutors had developed a “course presence” in other ways). By the second cohort, they produced a series of very short video to introduce the module, something that Professor Martin Weller reproduced for the Open University‘s Open Education MOOC. It is quite clear from these videos that Dr. Bill Cope has a lot of “classroom presence”, he is incredibly knowledgeable about his subject, his enthusiasm and good humour is infectious. I also really appreciated his occasional digressions looking at his many “educational heroes” to help reinforce his point that the e-affordances have been around for a very long time, if not by name. I would genuinely love to sit in on one of his actual lessons.

Video Lectures: The Bad

If I have a criticism (and it is rather a churlish one), it’s Dr. Cope’s wildly incessant gesticulation that is very reminiscent, to much older readers, of Dr Magnus Pyke. Whilst this wouldn’t look out of place in an actual classroom, it is something that is unfortunately magnified and amplified in the videos (which tend to operate within a very enclosed and intimate space) – so what had started out as being quite endearing trait in week 1, became quite annoying in week 3, and by week 6 I learnt to filter it out. Similarly, Dr Kalantzis appeared to look uncomfortable in front of the camera making little eye contact with the camera (i.e. the audience) and appeared to be looking down at her notes for most of the time. Presenting to a camera, and not a live audience, is very difficult to do and takes a lot of practice and confidence to pull it off, something I thought Professor Weller did very well for the Open Education MOOC. In many ways, we are asking our tutors to “perform” (as in “to entertain”) in front of the camera.

Video Lectures: The Ugly

I do have a bit of a gripe around quality control though, specifically around the closed captioning transcripts. In the main, these were great and very helpful; I assume these were generated on the fly by voice recognition software. However, the gripe is this: someone didn’t check that the transcripts matched to what was actually being said by the course tutors. For example, in the week 8 videos, Dr Kalantzis talks about “data”, but the software translates this as “daughter” (I suspect that the software might have had trouble with Dr Kalantzis’ Australian accent). The point being, these transcripts could have been manually edited and corrected – its the small things that matter.

Discussion Forums

If the videos are perceived as the core educational content, then the discussion forums are seen as the core communication channel. The e-Learning and Digital Cultures MOOC had attempted to flex the rigid platform structure of Coursera by adopting a more connectivist approach by utilising a range of social media platforms such as Twitter, Google+, Facebook and blogging tools in which the students who participate in. In this cohort, at least, the communication method is strictly the Coursera discussion forums. In the “Getting to know your classmates” forum, this registered approximately 440 “original” threads. For those of us who opted to embark on the Intermediate or Advanced levels of participation, week 1 (“conceptualising learning”) recorded around 144 original articles; by week 7 (“metacognition”) this has dropped to 62 original articles. However, this may not necessarily be a simple case of students just dropping out, it could be that student who start late may find it difficult to catch up with the rest of the cohort (Yang, Sinha, Adamson & Rose, 2013); or students are preferring to work at a slower pace or with selective engagement (Onah, Sinclair & Boyatt, 2014).

Opinion Polls

For most of the videos, a “What are you thinking?” opinion poll was added with three choices (this could have been conceived as a “bit of fun”). Two of which being at the polar opposites to each other. One option took a distinctly utopian opinion in which technology is perceived as having a positive effect. At the other end of the divide, the opinion is somewhat couched towards unsophisticated and non-technological tendencies – it was all a little bit too black or white for my tastes. Invariably, I opted for the third option that tended to say:

Ugh, it’s complicated, or it’s just too hard to say one of the first propositions is truer than the other…

CG Scholar

In addition to the Coursera platform, the course was also being “mirrored” on the Scholar platform developed by Common Ground Publishing. As the course convenors explain:

Not only are we researching and teaching about e-learning ecologies, we are involved experimentally in their development.

They have received research and development (R&D) funding from the Institute of Educational Sciences, the research arm of the US Department of Education, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in order to pursue this research. The students are encouraged to use both platforms, in part to aid their research on the design of e-learning ecologies; but also, to see how different kinds of peer feedback can be given. Cope (2015) suggests that Scholar could either be the “next generation Learning Management System” (LMS), or a platform that goes “beyond being a Learning Management System”. He draws a comparative analysis of Scholar with the main first generational (i.e. legacy) LMSs, that of Blackboard (1997); Moodle (2002); and Canvas (2008); unsurprisingly, Scholar “demonstrates” that it is able to support and sustain the notion of “New Learning” and, in particular, that of the seven affordances. Personally, I found Scholar a little clunky and was disappointed to learn that there were a number of comments to my posts and the system had not alerted or informed me in some way. I’m afraid I am not seeing what the course convenors see in the system.

Conclusion

I should reiterate that I genuinely enjoyed the course and the subject matter and that the course tutors were incredibly engaging and authentic. I did, however, raise an eyebrow over the mention of the Common Core State Standards Initiative, which doesn’t mean an awful lot if you are outside of the US; so there is something about making sure that cultural or country-specific contexts are kept to a minimal if tutors do not want to alienate their global student corpus. I have to confess that the picture that Drs Cope and Kalatzis painted during the course of eight weeks was somewhat utopian in character and tended to be aligned towards Primary and/or Secondary Education. I am not sure how well the “New Learning” philosophy would translate in Higher Education (HE) contexts. For one thing, certainly in the UK that is, HE does not have a common (or national) curriculum, so building such resources and content into LMS-type systems like Scholar, is going to be time consuming and resource hungry. Furthermore, “New Learning” presupposes that students will have ready access to PCs, laptops or tablet devices with “traditional” classrooms being reconfigured to be technology-rich in order to support and sustain such an enterprise. In austerity time, this could prove to be difficult. Students in the UK HE sector are currently paying as much as £9000/annum fees, they demand and expect, rightly or wrongly, to have face-to-face contact time with their tutors – though this, too, could be reconfigured so that the contact hours is much more meaningful, and not necessarily conducted through face-to-face interation (QAA, 2011a, 2011b ). The question is, then, what would students in HE make of the “New Learning” philosophy?

References

Cope, W. (2015). “The Trouble with Learning Management Systems”. Scholar User Group’s Updates, Scholar, 22.2.2015. Available at: https://cgscholar.com/community/community_profiles/scholar-user-group/community_updates/22789 [Accessed 10.3.2015].

Kalantzis, M. & Cope, B. (2012). New Learning: Elements of a Science of Education. 2nd Edition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Onah, D.F.O., Sinclair, J. & Boyatt, R. (2014). “Dropout Rates of Massive Open Online Courses: Behavioural Patterns”. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULEARN14), Barcelona, Spain. 7-9 July 2014. Available at: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/dcs/people/research/csrmaj/daniel_onah_edulearn14.pdf [Accessed 10.3.2015].

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2011a). Contact Hours: A Guide for Students. Gloucester, England: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. Available at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/publications/information-and-guidance/publication?PubID=44 [Accessed 10.3.2015].

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2011b). Explaining Contact Hours: Guidance for Institutions providing Public Information about Higher Education in the UK. Gloucester, England: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. Available at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/publications/information-and-guidance/publication?PubID=48 [Accessed 10.3.2015].

Yang, D., Sinha, T., Adamson, D. & Rose, C.P. (2013). “‘Turn on, Tune in, Drop out’: Anticipating student dropouts in Massive Open Online Courses”. In: NIPS Data-Driven Education Workshop, Harrah Hotel, Nevada, USA. 10 December 2013. Available at: http://lytics.stanford.edu/datadriveneducation/papers/yangetal.pdf [Accessed 10.3.2015].