A few months ago a member of my EdD cohort had set up a WhatsApp group so that we could keep tabs with each other, ask questions, and generally offer support to each other as and when we needed it.

A Rough Ride

We all knew that the doctorate programme of study was not going to be easy, and in many ways it is the intellectual equivalent of running a 26 mile marathon or climbing Mount Everest. It’s tough. Very tough. As every athlete will tell you, you need to pace yourself and stay focused. Some days, it is easier said than done. As many doctoral students have said before us and I am sure they will continue to say this long after we have finished: You make a lot of sacrifices along the way. It is not just the clock you are up against. Friends, family, colleagues, and work are all stacking up (unintentionally) against you. They want a piece of you. They want some of your time. You feel mean and guilty if you don’t give it to them. Striking that work-life-study balance does not come easy.

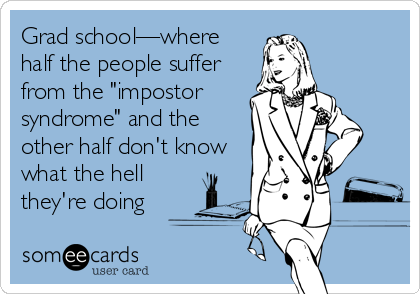

This week saw a brief exchange between some of them as they struggled to get on top of their research or reading because life (once again) has a bit of a nasty habit of intruding upon you when you least want it to. Strong feelings of self-doubt, and getting caught out as being a “fraud” or “imposter” started to bubble to the surface as the perceived enormity of the doctorate enterprise begins to take hold with cold, clammy vice-like tentacles around one’s fragile and fractured confidence.

On a rational level, none of us would have got this far if our tutors and supervisors didn’t think we were up to the intellectual rigours of doing a doctorate. We just would not have been allowed to have proceeded thus far. Unfortunately, one’s rational side is not always present when gripped by the fear of failing or being a failure. I suspect, it is only just a suspicion mind you, that there are some on my EdD cohort who hold me up as someone who is confident, knowledgeable, and knows where they are exactly heading with their EdD thesis. It may come as a surprise (or not) to them to learn that I have episodes where I haven’t a clue what I am doing or where I am going as I spiral downwards around and around in my own personal “Slough of Despond” (Bunyan, 2008, [1678, 1684]) where my educational ‘demons’ lie in waiting to tease and torment me. This is something that I had already alluded to once or twice on this blog.

The Imposter Syndrome

So, yes, I too feel like an imposter or a fraud at times. Such a feeling can be perceived as a “violent act against one’s authentic self” (Vanzant, 2013). But, it seems that I and some of my EdD peers are in “good” company as it were: Neil Gaiman (writer), Tommy Cooper (comedian), Don Cheadle (actor), Chuck Lorre (scriptwriter), Emma Watson (actress), Tina Fey (comedienne), Chris Martin (singer-songwriter), Jodie Foster (actress), Kate Winslet (actress), Maya Angelou (writer), Henry Marsh (neurosurgeon), Natalie Portman (actress), amongst others have all professed their insecurities and struggles with imposter syndrome (Jarrett, 2010).

The impostor syndrome refers to a high-achieving individuals who have an inability to internalize their personal accomplishments coupled together with feelings of being exposed as a ‘fraud’. Despite overwhelming evidence to suggest that this person is highly competent, they will dismiss it as being down to good luck or timing, or that they have deceived others into thinking they are more intelligent and competent than they believe themselves to be. Early studies suggested that imposter syndrome was particularly common among high-achieving women (Clance & Imes, 1978), whilst later studies have indicated that men are as equally affected as women (Matthews & Clance, 1985).

Jungian Psychology

Some psychologists have suggested that of the Jungian psychological types (Jung, 1971), the introvert is probably the one that is prone to the imposter syndrome as they “keep important aspects of their personality hidden from the world” and that they describe themselves as being “shy, anxious and … having low self-confidence” (Langford & Clance, 1993, pp. 496-497). Furthermore, the Jungian archetype (Jung, 1969) of the shadow, which is described as being:

… that hidden, repressed, for the most part inferior and guilt-laden personality whose ultimate ramifications reach back into the realm of our animal ancestors and so comprise the whole historical aspect of the unconscious (Jung, 1969, para. 422, p. 266)

This “shadow” could also be seen as a contributing factor towards experiencing these fraud inducing episodes. It comes as no surprise to learn that my Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) registered me as belonging to the INFJ-A personality type. This particular personality type is said to be “very rare, making up less than one percent of the population”.

What Next?

So where does this take me and my EdD peers who suffer from panic pangs in fear of receiving a knock at our respective doors from the Fraud Squad? In an interview with Dr Stephen Brookfield (Ancowitz, 2013), he suggests that people ought “own up to it” and talk about it more, something that has been suggested elsewhere (BBC, n.d.). He also admits to “thinking” of himself as an imposter, but imparts some wonderful advice:

I would not want to work with anyone who didn’t have a healthy touch of impostership, because it keeps you humble and focuses you on improving your practice. Without this syndrome, lies a megalomaniacal belief in your own infallibility!

Incidentally, I saw Dr Brookfield give a talk entitled What Does It Mean To Think And Act Critically at my university in June 2011. He hid his “impostership” well.

It may be useful keeping a file of people who say nice things about you. I recently got nominated for a Golden Apple Award which took me by total surprise. I was very humbled by it and asked for the citations that got me nominated in the first place. Next, you can try and avoid comparing yourself with others, it is neither healthy nor helpful. Accept failure and use it as a valuable learning experience. Accept that you are not the only one who doesn’t know what they are doing … there are millions of us out there who don’t what we are doing.

As I am slowly finding out, I am not alone in this. If they are reading this, I hope my EdD peers realise that they are not alone too!

References

Ancowitz, N. (2013) ‘Managing Your Impostor Syndrome: What to do if you feel like a fake’, Psychology Today, 17.4.2013. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/self-promotion-introverts/201304/managing-your-impostor-syndrome [Accessed 11.6.2016].

BBC. (2016) ‘Why feeling like a fraud can be a good thing’, BBC News Magazine, 25.4.2016. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36082469 [Accessed 11.6.2016].

BBC. (n.d.) ‘How do I stop feeling like a fraud?’, BBC iWonder. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zgsv9qt [Accessed 11.6.2016].

Bunyan, J. (2008, [1678, 1684]) The Pilgrim’s Progress: From this World to that Which is to Come. Edited by R. Pooley. London, England: Penguin Classics.

Clance, P.R. & Imes, S.A. (1978) ‘The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention’, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 15(3), pp. 241–247. doi: 10.1037/h0086006.

Jarrett, C. (2010) ‘Feeling like a fraud’, The Psychologist, 23(5), pp. 380-383. Available at: https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-23/edition-5/feeling-fraud [Accessed 10.6.2016].

Jung, C.G. (1954) ‘The Development of Personality’, in Read, H., Fordham, M. & Adler, G. (Eds) The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 17: Development of Personality. London, England: Routledge.

Jung, C.G. (1969) ‘Conclusion’, in Read, H., Fordham, M. & Adler, G. (Eds) The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2): Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. London, England: Routledge.

Jung, C.G. (1971) ‘The Introverted Type’, in Read, H., Fordham, M. & Adler, G. (Eds) The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 6: Psychological Types. London, England: Routledge.

Langford, R. & Clance, P.R. (1993) ‘The Imposter Phenomenon: Recent Research Findings Regarding Dynamics, Personality and Family Patterns and their Implications for Treatment’, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 30(3), pp. 495-501. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.30.3.495.

Matthews, G. & Clance, P.R. (1985) ‘Treatment of the Impostor Phenomenon in Psychotherapy Clients’, Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 3(1), pp. 71 81. doi: 10.1300/J294v03n01_09.

Vanzant, I. (2013) Forgiveness: 21 Days to Forgive Everyone for Everything. Carlsbad, CA: Smiley Books.